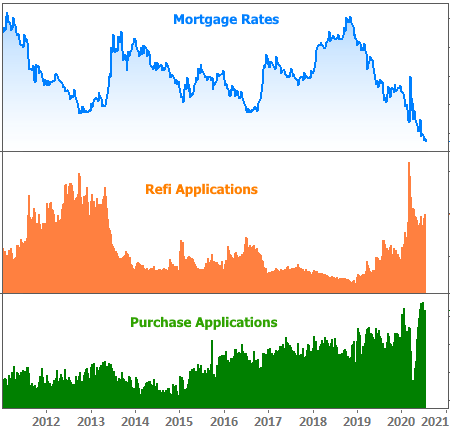

The bond market saw yet another week with rates in a holding pattern at historic lows. With coronavirus being the primary motivation for rates, it wouldn’t be a surprise to see indecision continue until we get a clearer idea of how things will shake out with respect to the pandemic vs the global economy.

In fact, apart from the all-time low mortgage rates, things have been downright boring when it comes to the underlying bond market driving those rates. Absent a vaccine-related breakthrough, there’s not much for the bond market to do besides hurry up and wait. After all, even if there is amazing news about a vaccine trial, that’s only worth a smaller-scale, shorter-term bump for markets until the stuff actually makes it into widespread circulation and proves its worth.

Between now and then, we can expect to see the bond market drift in a similar range and make modest course corrections depending on the covid outlook. We can also dig into the nuts and bolts of the mortgage bond market to ask and answer questions about how low rates can eventually go. The answer is actually surprisingly simple.

So, how low can rates go?

The lowest conventional 30yr fixed mortgage rates would have a very hard time falling below 2.25% unless covid immunity proves to be impossible. This isn’t a guess or a prediction, like most comments about financial market potentialities. Rather, it’s simply the hard floor based on the structure of the mortgage bond market–at least for now.

Mortgages are like eggs.

Mortgage bonds are comprised of numerous individual mortgages. Think of these bonds like egg cartons and think of individual mortgages like eggs. You don’t often see single eggs being sold in the store. But a dozen or more similarly-sized eggs are much more marketable in the confines of their carton.

Eggs come in many sizes and colors. There are certainly egg sizes somewhere in between medium and large, but there are no carton sizes between medium and large, only thresholds that determine the biggest and smallest eggs that can still be labeled as any given size/type.

It’s exactly the same story for mortgage bonds. Very few mortgages are exactly alike, but those that are similar enough end up getting placed in the same carton. In the bond world, those cartons are known as coupons, and indeed, they have a threshold as to the loans they can contain depending on the interest rate.

2.25% is the smallest “egg” allowed into the carton.

Right now, the lowest actively-traded coupon allows for rates no lower than 2.25% (conventional 30yr fixed). This is as far as rates could fall without facing significant resistance. In fact, the best-case scenario rates have only just broken below 3% and we’re already seeing them struggle to improve.

This is logical for a few reasons. First off, mortgage rates are only capable of falling so quickly before it begins to cause major problems for the industry. At issue is the ability of mortgage investors to earn returns. If new loans only generate a few payments before refinancing, investors lose money. That leads to lower investor demand and higher mortgage rates.

What about the rest of the supermarket?

If mortgages are like eggs, they would be like the higher-priced specialty eggs. US Treasuries would rule the roost as the most widely-distributed plain old egg (aka the leading representative of “the broader bond market”). What happens to Treasuries has historically had a direct effect on mortgage rates just like speciality egg prices could be affected by egg prices overall.

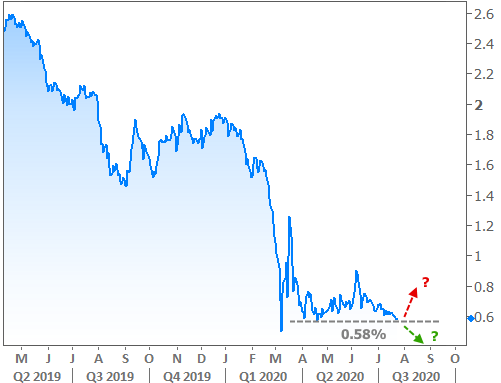

Treasuries suggest headwinds as well. Mortgage rates are finally mostly caught up to where Treasuries say they should be. We can see this in the following chart which shows the average daily 30yr fixed mortgage rate versus 10yr Treasury yields. Coronavirus threw the relationship out of whack, but during calmer times, these lines follow each other almost perfectly (which is why many believe mortgages are based on the 10yr yield).

So why does it matter if mortgages have closed that gap with Treasuries?

Simply put, there’s a risk that Treasuries are seeing some resistance to further improvement–a “floor” in other words. It’s worth noting that these sorts of floors are broken all the time and by no means do they predict the future. But in this case, we know we’ll need to see things get worse for the pandemic and domestic economy in order for this floor to be broken in a major, sustainable way. That’s a double-edged sword for the mortgage and housing markets, which thrive on a combination of low rates and positive attributes like stronger consumer sentiment and low unemployment.

That’s why things are as good as they are at the moment. There’s still a good amount of optimism as to how the economy may bounce back from the recent trauma. Evidence of a “double dip” recession–something that could help rates move even lower–has yet to materialize. Economic data continues to improve in general, especially in the housing market.

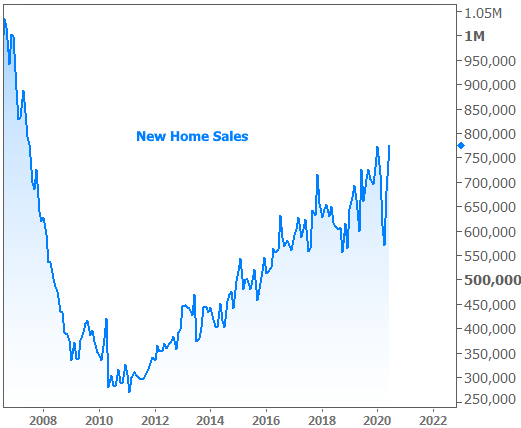

In fact, the Census Bureau reported this week that New Home Sales rose to their highest levels since before the financial crisis.

Take this one with a grain of salt for a few reasons. There’s a wide margin of error with this data. More importantly, New Home Sales have had to pick up a lot of slack from existing homes as individual sellers are less interested in marketing their homes during the pandemic than builders who can sell new, clean, vacant homes. Case in point, the National Association of Realtors also released Existing Home Sales data this week, and it hasn’t recovered nearly as much of its previous highs.

Make no mistake though: there is a very strong level of demand out there right now. Mortgage application data confirms that (and also suggests all-cash buyers may be holding off on real-estate post-covid).

In the week ahead, markets will continue taking cues from coronavirus headlines, but there are several important events. The Fed will release its newest policy announcement on Wednesday, and while they’re not expected to make any changes, their characterization of the economy and their plan of attack always has the potential to move markets. A day later, we’ll get the first official report on Q2 GDP. Investors know it’s going to be a very big, very negative number (current median forecast = -34%). This may or may not produce much of a response in markets, depending on how close the number is to those forecasts.