This week’s most prominent news was the so-called “official” beginning of the trade war between the U.S. and China. For something so official, it left much to be desired in terms of market movement. Let’s sort out what’s real, what’s not, and where our focus should be.

So is there a trade war?

Yes, to whatever extent new U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports and China’s retaliatory tariffs on U.S. imports constitute a trade war, it’s now official.

Why isn’t that big news?

These tariffs were announced in the middle of June. Markets have been bracing for impact ever since. This week simply marks the start of enforcement at the operational level.

And China retaliated?

After the mid-June announcement from the U.S., China immediately threatened to retaliate with an equal amount of tariffs. With the U.S. making things official this week, China simply did the same.

What was the reaction?

Because the “official” news was so old and so clearly spelled out, there wasn’t much left for financial markets to do besides watch how other investors were trading. After fearing the worst, traders saw that other traders weren’t panicking. With additional help from Friday morning’s jobs report, stocks moved quickly higher.

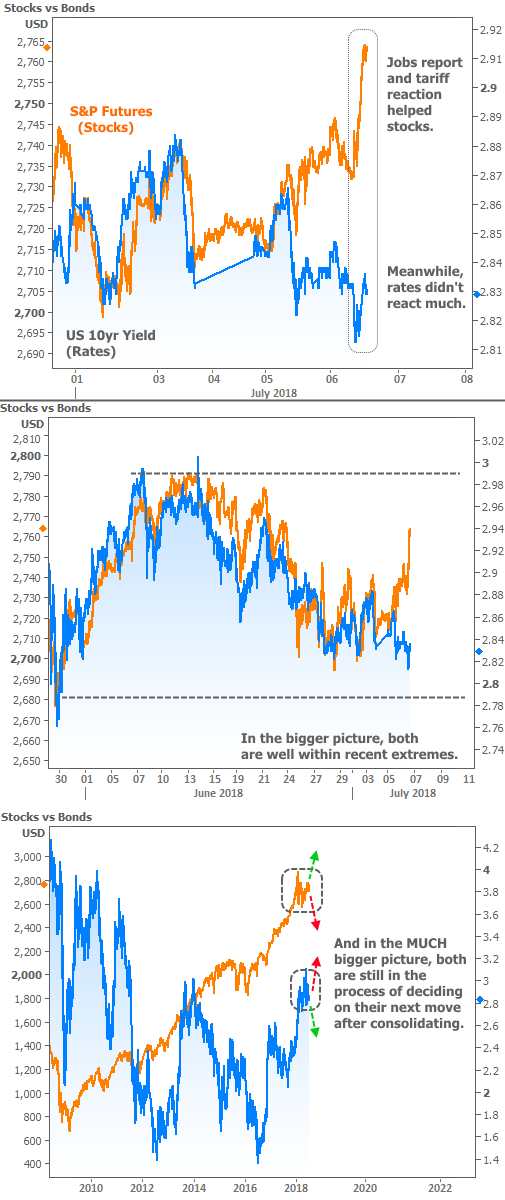

That improvement can be seen at the top of the following chart. The lower 2 sections of the chart put this week’s movement in perspective.

In other words, both stocks and bonds are still very much inside their CONSOLIDATION patterns that we discussed in last week’s newsletter.

What’s up with that? What does that have to do with the trade war?

Markets remain in those consolidation patterns because a “trade war” is a concept. While dollar amounts can be attached to policy changes, both sides have threatened additional tariffs. The tariff amounts could easily change. More importantly, even if the amounts were set in stone, markets still can’t be sure of the long-term effects.

Was there any damage? Can you relate this to the housing/mortgage market?

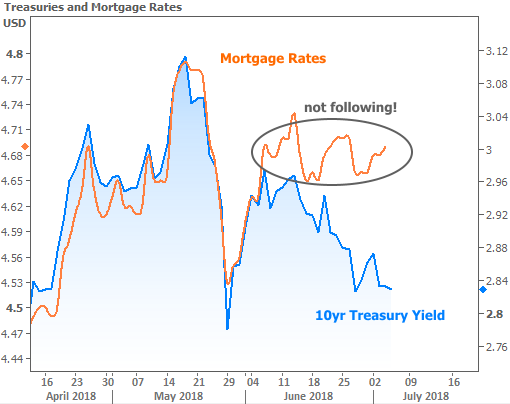

Unfortunately, mortgage rates have been one of the notable casualties of the recent volatility. Unlike US Treasuries, whose prices/rates are set by supply and demand in the open market, mortgage rates are only MOSTLY based on supply and demand in the open market! Volatility costs lenders money, which is one reason mortgage rates haven’t been able to follow Treasuries’ lead since mid-June:

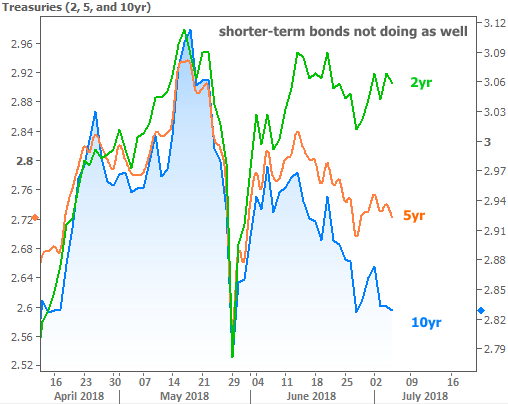

Another factor is the structure of the bond market and the typical behavior of mortgage borrowers. By “structure,” I’m referring to the array of available maturities (i.e. 2yr, 5yr, 10yr, 30yr Treasuries). Investors treat these maturities differently over time. At present, longer maturities are in fashion and shorter maturities are being shunned. Simply put: everyone wants to own 10 and 30-year bonds as opposed to the sub-5yr stuff.

And how does that affect mortgage rates?

Mortgage rates are based on Mortgage-Backed-Securities (MBS). These are the bonds that groups of mortgages “turn into,” essentially. They’re then traded among investors on the open market (like corporate bonds or municipal bonds, etc.).

In deciding whether a certain bond is a good investment, traders use Treasuries as a yardstick. Treasuries are good for that purpose because they are virtually risk-free, abundant, actively traded, and exceedingly simple.

Duration (the length of time a bond will last) is one of the most important points of comparison. Bonds that last about 10 years are considered against 10yr Treasuries; those that last 2 years against 2yr Treasuries, and so on.

Most bonds have a set duration, making the comparison very easy. But MBS are naturally dependent on human behavior. If rates fall, people may refinance in greater numbers. That would cause the average duration to decline.

While we can’t know if rates are about to fall in general, we doknow that analysts don’t anticipate the average mortgage will stick around for 10 years. To put it more simply, mortgage-backed-securities (and thus, mortgage rates) aren’t keeping pace with the 10yr Treasury yield because they’re seen as having a shorter duration in an environment where longer duration is in favor.

A chart of shorter versus longer maturities in Treasuries helps paint the picture.

OK, last question: why aren’t investors worried about mortgage rates moving higher, thus making duration INCREASE? Wouldn’t increased duration be good for rates in this environment?

Great point! If investors thought MBS would last more than 10 years, mortgage rates wouldn’t be lagging as much. But they’d still be lagging due to lender strategy. Lenders are operating on very thin margins and the cost associated with guaranteeing rate locks is higher amid uncertainty and market volatility. Those costs are passed on to borrowers in the form of higher rates.

Additionally, investors have already done a lot to value bonds based on higher rates looking nearly inevitable for most of the past 2 years. As the trade war raises doubts about that inevitability, investors are shifting to account for the risk that rates could actually fall enough to stir up refi demand (and thus, shorter durations for MBS).

It’s a bit abstruse, but the moral of the story is that the “possibility of low rates in the future” is a competitive disadvantage today. Tying this all together, we can definitely count the trade war narrative as a key source of uncertainty and a key reason for consolidations seen in stocks and bonds. As its effects become clearer, so too will the next wave of momentum in rates.