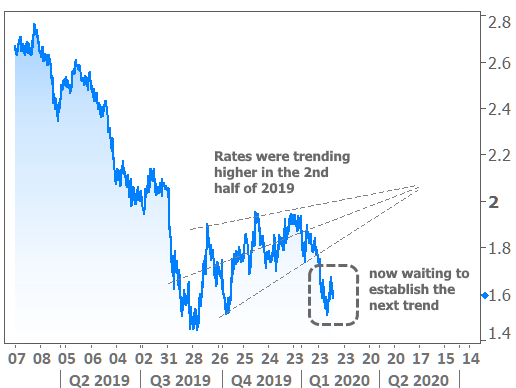

As interest rates moved in an ever-narrower pattern in the 2nd half of 2019, we looked to early 2020 to break that cycle, for better or worse. So far, 2020 has delivered on the promise of increased volatility, but not for the reasons anyone expected.

There was a far better case to be made for the risk of rising rates in the new year. This had to do with their recent, extended stay at long term lows–largely due to trade war uncertainty–coupled with the fact that trade war uncertainty was beginning to clear up.

While there was a bit of upward pressure on rates surrounding the phase 1 US/China trade deal, those concerns quickly took a back seat to January’s unexpected events. The threat of a US/Iran war briefly sent shockwaves through the market earlier in the month, but ever since then, the coronavirus outbreak has been the dominant consideration for the bond market (which, of course, dictates interest rates).

In short, the coronavirus effect abruptly put an end to the trend of rising rates that had been in place ever since the trade war ushered in long-term lows last summer. This can be seen in the following chart of 10yr Treasury yields, which serve as an important benchmark for longer-term interest rates like mortgages.

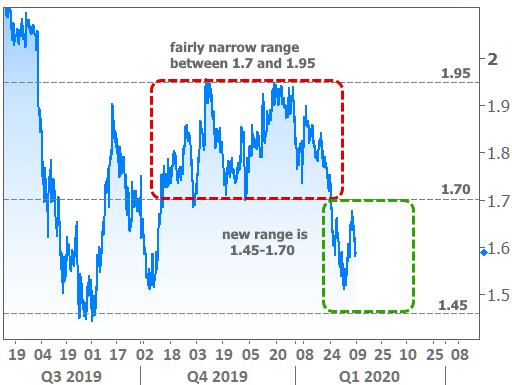

Looked at another way, we could simply say that rates were favoring the higher end of their post-trade-war range, marked by 10yr yields of 1.70% through 1.95% and that coronavirus brought them back into the lower half of the post-trade-war range.

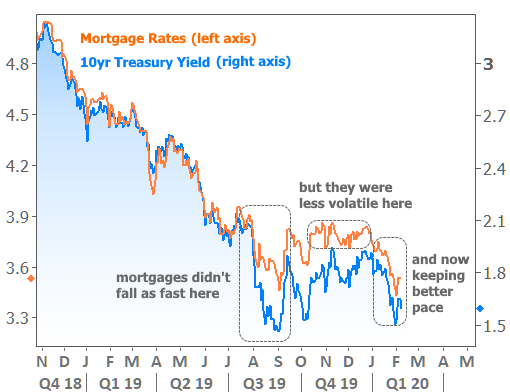

Mortgage rates have been moving in a similar direction to Treasuries during this time, but not always in lock-step. This first became readily apparent as rates plummeted in August. Mortgages were lower, yes, but not nearly as quickly as Treasury yields. That ultimately proved useful, however.

As Treasury yields began to rise, investors started worrying about a big bounce in rates, but mortgages were able to remain more calm by comparison. This improved the flow of business both for purchases and refinances. It also allowed time for the mortgage market to adjust to the new rate range and position itself to take better advantage of the next move. That’s exactly what’s happened over the past 3 weeks as the average 30yr fixed mortgage rate managed to drop at a much more comparable pace to Treasury yields.

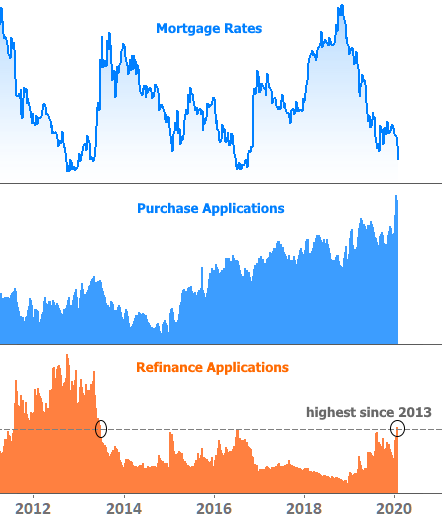

All of the above adds up to a fairly intense level of activity in the mortgage market. Purchase apps may have lost a small amount of ground this week, but overall (and in annual terms), they continue to push post-crisis records.

Refi apps may never make it back to the post-crisis records seen during the golden age of low, stable rates in 2012, but they just hit the next most impressive milestone by breaking 2016’s weekly application record. That qualified as a “refi boom” then, and it qualifies now.

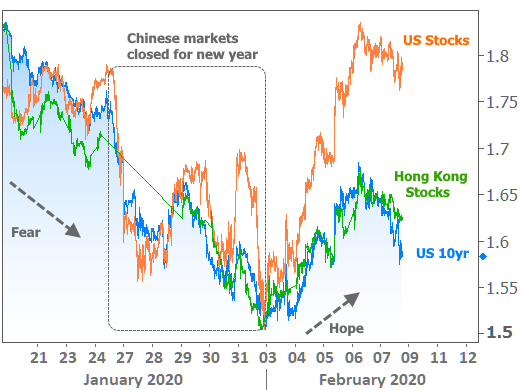

How long can this last and how low could rates go? Accurately answering that question requires clarity on the coronavirus outbreak. Granted, this isn’t the only consideration for rates, but it’s definitely still the biggest one. The bottom of the recent move in rates coincided perfectly with the peak level of uncertainty in mainland China’s financial markets (which were closed for the new year holiday at the end of January).

As soon as US markets could get a clear read on China’s market response, fear was replaced with hope, momentum turned on a dime, and rates began to head higher. (NOTE: in the chart below, Hong Kong’s stock exchange is used in order to show more market activity, and it reopened several days before mainland China’s Shanghai index).

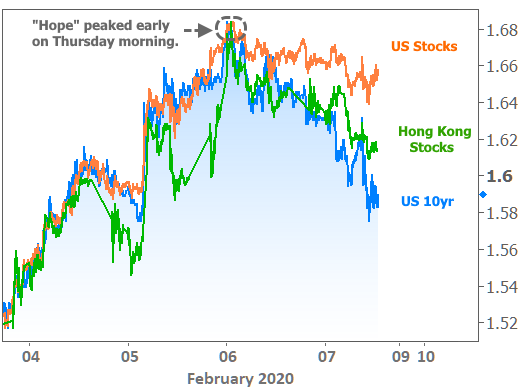

If you’d asked the average market analyst on Wednesday, they would have been more likely to tell you the coronavirus move was over and markets were beginning to correct back in the other direction. But then this happened:

In other words, the drama has yet to play out. The first 3 days of the week represented more of an ‘opening of floodgates’ that allowed traders to get a better read on China’s market response. They were prepared for the worst and found that they were just a bit over-prepared. The past 2 days suggest that “fear” has yet to be permanently replaced by “hope” with respect to coronavirus.

When that happens (and it will), traders will still be asking themselves what the lasting economic impact will be. As always, if the global economy is weaker than expected, upward pressure on rates will be limited. That said, some measure of upward pressure is still the baseline assumption. So at the very least, those who don’t want to miss out on this refi boom should probably get their ducks in a row sooner than later.