A monthly report on new residential construction came out this week, showing a big drop in housing starts (the groundbreaking phase following a building permit). Should we worry about a slowdown in home sales?

The short answer is “no.” The long answer is a bit more nuanced, but in both cases, we’re certainly not standing on the edge of the sort of cliff seen in 2008.

In the chart below, we can see the drop in Housing Starts on the far right. At face value, it was disconcerting because it was the biggest drop in more than a year, but that’s really the extent of the bad news.

Big drops in housing starts happen from time to time. And despite this particular drop, a positive trend remains intact.

On a more substantive note, building permits didn’t have nearly as bad of a month (they fell only 2.2% compared to a 12.3% slide in housing starts). Volatility in ‘starts’ doesn’t mean much unless it’s accompanied by a similar slide in permits.

But let’s not just assume it’s random volatility and simply hope it goes away next month. Let’s dive deeper so we can put our minds at ease.

Fortunately, diving deeper is pretty simple. The first red flag is the fact that the Midwest region experienced a decline that was nearly 4 times as big as the next closest region. That’s too big to chalk up to random volatility in market data.

Indeed, it was not random! If you’re from the Midwest or if you keep tabs on the weather across the country, you know June was a crazy month for some of the largest metro areas. Record high temperatures juxtaposed with flash floods understandably put a crimp on builders’ plans to break ground.

This accounts for the lion’s share of the drama in housing starts. In other words, if we factor out weather-affected areas, June’s declines wouldn’t be cause for concern.

If blaming it on the rain isn’t quite enough for you, just consider new home sales in the context of total home sales. The following chart shows that actual new sales numbers (not housing starts) are still trending higher. Existing home sales are trending sideways in healthy territory (more than 5 million units per year). When we put new and existing home sales on the same axis, we can see how they stack up against each other.

Bottom lines:

- Builders didn’t meaningfully slow down their permittingefforts

- Groundbreaking efforts were certainly affected by the weather

- Weather caveats aside, new homes are a much smaller piece of the pie when it comes to overall home sales numbers

- More importantly, home sales numbers haven’t yet been affected (the alarming data pertains solely to groundbreaking)

While the housing news ends up being much less exciting by the time we break it down, the week wasn’t a total bust in terms of drama. The most sensational news dealt with the President commenting candidly on the Fed’s rate policy. This is uncommon, to say the least. The Fed is designed to operate independently and without regard for the preferences of lawmakers (except inasmuch as lawmakers nominate and confirm Fed officials, but we’re nowhere close to a shake-up in that regard).

Trump essentially said he doesn’t want the Fed to keep hiking rates. The comments made waves because they were so unconventional, but they ultimately didn’t have a huge effect on markets. Lots of people would like the Fed to stop hiking rates, but the Fed’s hands are tied by current economic realities. If the president tries to untie them, the fallout would likely be severe–so severe as to make it highly unlikely.

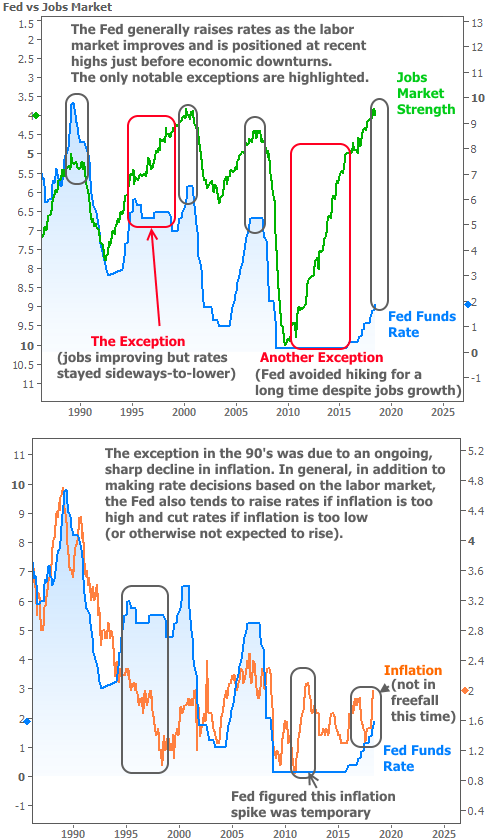

The following is not required reading, as it’s a bit technical, but for those who want to understand why the Fed’s hands are tied, consider the following chart. It shows the Fed Funds rate compared to the strength of the labor market and inflation. In general, the Fed can raise rates as employment and inflation increase. The only notable instance where the Fed kept rates steady in the face of rising employment was in the late 90’s when inflation was plummeting.

In other words, the Fed kept rates steady in order to combat falling inflation (too much is a bad thing, just ask Japan). Contrast that to the present economic cycle where inflation is at 7 year highs, and the Fed only has one more reason to continue raising rates. At the very least, there is no 90’s-style justification to keep rates flat in the face of 4% unemployment.

(Note: the spike in inflation in 2011 was a byproduct of the super low inflation during the Great Recession, and thus NOT something that would force the Fed’s hand. The Fed rightfully assumed that spike was temporary).