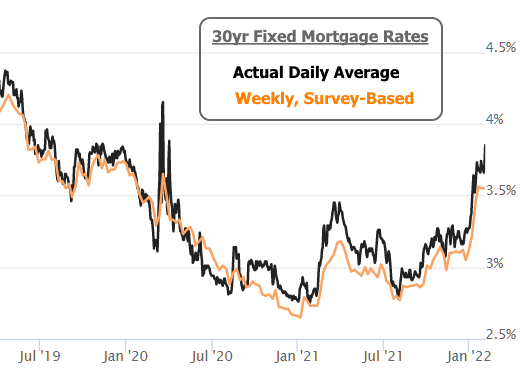

Rates have been trending higher in fits and starts since August 2020, but the mortgage market was insulated from much of the pain due to its disconnect from Treasuries in 2020 (they typically correlate very well). In fact, mortgage rates were falling throughout the 2nd half of 2020 while 10yr yields were steadily rising.

As we predicted, expected, and warned, 2021 saw the correlation return despite a few divergences due to things like mortgage-specific fee changes. By the end of 2021, both Treasury yields and mortgage rates were moving higher with a purpose.

Enter 2022, and with it, a fairly big shift in tone from the Federal Reserve regarding the pace at which it will be removing accommodation (fancy words for “doing things that aren’t helpful for interest rates“). That made January one of the worst months for mortgage rates of the past decade, but more of the damage was seen at the beginning of the month.

Over the past few weeks, we could make a decent enough case that rate momentum had leveled off and was drifting sideways. That’s not an uncommon development after a big spike. The market might do this to catch its breath before the next move higher, or to signify a supportive ceiling before a moderately friendly correction. Such things aren’t decided ahead of time. They happen in response to ongoing input from data and events that matter to rates.

The big monthly jobs report is something that typically matters a great deal to rates. Oddly enough, Friday’s jobs report was NOT seen having much of an impact for a few reasons. First off, analysts expected a much weaker number due to Omicron’s likely impact. Moreover, the Fed is almost exclusively focused on inflation right now as opposed to the labor market (employment and prices are the 2 key parts of the Fed’s job description). In short, no matter what today’s jobs numbers turned out to be, they weren’t likely to impact the market’s view of the Fed’s reaction.

All of that is now out the window, sort of. Although there are several important caveats regarding major seasonal adjustments, the jobs numbers were so much higher than the average forecast that markets were forced to respond. Fed rate hike expectations increased briskly and bond yields surged to their highest levels in more than 2 years.

If we disregard the once-in-a-lifetime volatility seen in March 2020 (and we absolutely should), today’s mortgage rates are now in line with the highs seen in October 2019. On Friday alone, the average lender was an eighth of a point higher day-over-day, and more than a full percentage point higher versus the August 2021 lows. Many less than perfect loan scenarios are seeing rates over 4%.

NOTE: mainstream rate tracking surveys have NOT yet caught up with this move. Freddie Mac’s weekly survey, for instance, was published on Thursday and is based largely on the rates that were available this past Monday. Quite a bit has changed since then…

Getting back to the matter at hand, why were markets so surprised by the jobs report and is that the main reason for all the drama? The answer is both simple and complicated.

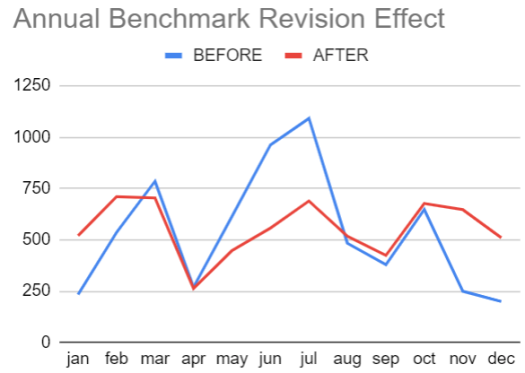

The complicated points surround the parsing of the more arcane aspects of the jobs data. Specifically, January’s data (reported in early February) always coincides with annual revisions to the Labor Department’s seasonal adjustment benchmarks. In the current case, those revisions acted to smooth out a volatile year of jobs data. In so doing, they made the middle of 2021 look a lot worse and the past few months look a lot better.

In addition to the payroll counts, markets also keyed in on a strong showing in the unemployment rate. Granted, it was higher than expected (4.0 vs 3.9), but the labor force participation rate moved up 0.3%. That means the rise in the unemployment rate is explained by workers returning the workforce more than 3 times over.

This is a surprising turn of a events on a month where omicron was supposed to result in rampant absenteeism. But not only are we dealing with seasonally adjusted numbers, the survey that drives the unemployment rate was also subject to revisions based on population growth.

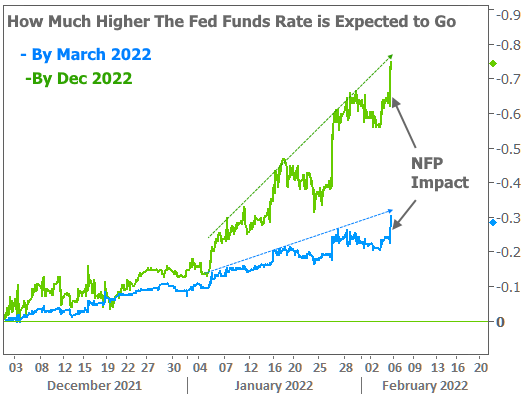

Looking past the data points affected by the revision process, some pundits suggest that strong wage growth increases inflationary risks and forces the Fed to consider faster rate hikes. Indeed, when we look at Fed Funds Futures (securities that allow traders to bet on future levels of the Fed Funds Rate), we can see on obvious spike after the jobs data (referred to in the chart as NFP for the ‘nonfarm payrolls’ component that headlines the report).

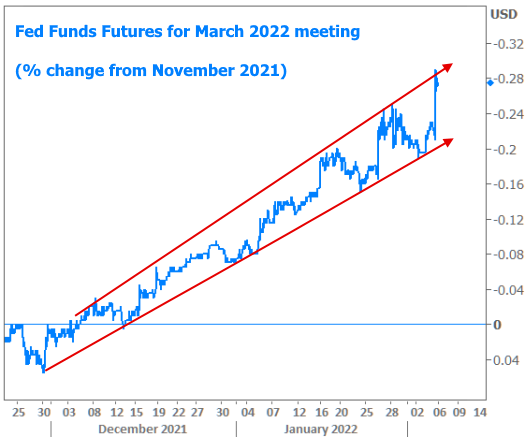

If you’re noticing that this week’s spike fits nicely in the longer term trend, you’re already seeing what matters. We can isolate the March meeting expectations to make it easier to see.

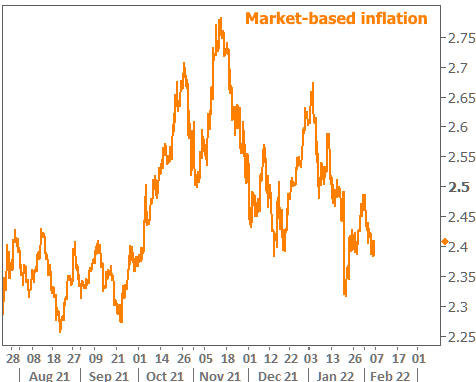

We can push back on this inflation narrative more decisively by examining recent changes if market-based inflation expectations. Not only are they lower this week, but they’re significantly lower since November. If traders were truly freaked out by wage-driven inflation implications, this number would have jumped after the jobs report.

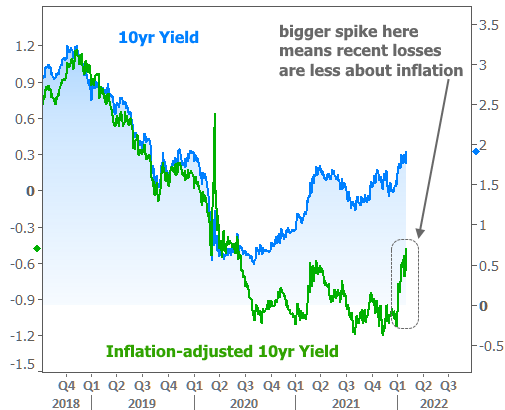

In fact, most of the recent run up in rates is due to NON-inflation-related components of bond yields. The following chart shows actual 10yr yields and the inflation-free component of 10yr yields (determined by inflation-protected bonds).

The fact is that rates have been moving higher since August 2020, and abruptly higher in 2022. They’d cooled off in a sideways consolidation pattern in the past few weeks and today delivered enough of a nudge to challenge the boundary of that consolidation. When breakouts like this occur in the bond market, they’re often followed by additional momentum in the same direction.

The other fact is that we can look at the past month as a sideways-to-slightly-higher grind in bond yields. The pace of increases suggested by the lower boundary of this range was not even broken by Friday’s yield spike.

So rates are rising… We get it… But how much worse could things get?

As is always the case, if the market knew for sure, it would already be there. Deceptive bounces are possible in the short term even as pressure remains toward higher rates in the long term. Eventually, things will turn around, but we don’t have any great precedent for how rates should normalize after a pandemic. At the very least, the most recent example of a longer-term rising rate environment serves as an important reminder that rates could easily go higher before the big turn.