While weeks in 2022 have been terrible for mortgage rates, we’ve always been able to say “at least it wasn’t as bad as that one week in 2013.” We can’t really say that anymore.

Sharply higher rates out of the gate on Monday, a few hopeful days mid-week, then another terrible day on Friday.

Why is all this happening?

It’s both simple and complicated. The simple part of the explanation has to do with the Federal Reserve (the Fed) making several unexpected adjustments to its policy outlook. Fed policy involves setting the key overnight lending rate in the US as well as deciding how to buy and sell large amounts of certain bonds.

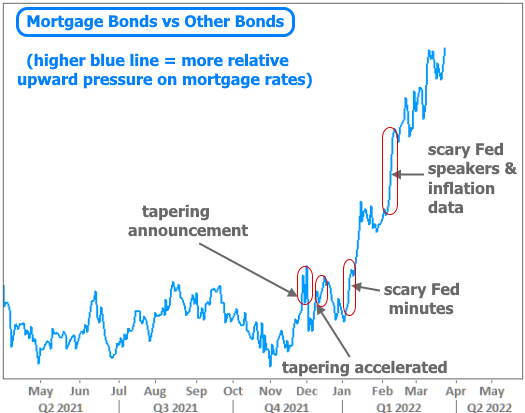

In addition to US Treasuries, those “certain bonds” include mortgage-backed-securities (MBS), which directly dictate mortgage rates. As such, the Fed bond buying outlook has a very big impact on mortgage rates. If the Fed gives the market a reason to expect smaller MBS purchases, rates rise. The bigger the surprise, relative to previous expectations, the bigger the reaction in the mortgage market.

Starting in November, the Fed began reducing the size of the bond purchases that began at the start of the pandemic. This was bound to happen at some point, but November was a bit earlier than some of the market expected. As a result, MBS suffered.

Then in December, the Fed announced it would decrease MBS purchases at a faster pace. This wasn’t really the end of the world at the time, because even after the Fed completely eliminated its scheduled bond purchases, they would still be reinvesting the proceeds from previous investments.

That sounds complex, but a simple example should clear things up. Imagine the Fed is your mortgage lender. As you make payments, or if you sell/refi and pay your loan off completely, the Fed will take that money and use it to lend to someone else. This is exactly what’s happening with the Fed’s “reinvestments,” but on a grand scale.

In this way, the Fed is not buying any NEW MBS. They’re simply replacing MBS that would otherwise fall off its balance sheet. These reinvestments account for a substantial amount of buying demand in the bond market, and “bond buying demand” = lower rates, all other things being equal.

Last time Fed bond buying fell to “reinvestment only” status, it took YEARS for them to finally put caps on reinvestments each month. In so doing, they began to gradually shrink their MBS holdings. The technical term for this is “balance sheet normalization” or simply “normalization.” Mortgage rates didn’t love the idea, but it was gradual enough to be tolerable. Plus, the market had years to prepare.

On January 5th, 2022, the “minutes” were published from December’s Fed meeting (this is the normal timeline for Fed announcements, with “minutes” following exactly 3 weeks later). The minutes can reveal additional details that didn’t make it into the official policy statement, and that’s exactly what happened in this case.

The market learned the Fed was discussing shifting gears into the balance sheet normalization phase MUCH faster than precedent suggested. To make matters worse, the committee had been discussing a faster pace of rate hikes than markets expected. Granted, the Fed Funds Rate doesn’t directly dictate mortgage rates, but if the market suddenly expects more/faster hikes, interest rates tend to move higher across the board.

The following chart helps us visualize this in terms of the mortgage market. The higher the blue line, the higher mortgage rates are moving relative to other rates (for bond experts who want the technical explanation, this is MBS yield vs Treasury yields with comparable duration).

As mentioned in the chart, scary inflation data is a problem for the Fed’s rate hike outlook because controlling inflation is one of the Fed’s 2 key policy goals. Incidentally, the other part has to do with “full employment” but since there are more than 100 jobs out there for every 60 people without one, the Fed is understandably just focusing on inflation at the moment. And inflation is… well… you’ve heard.

When something happens that increases inflation expectations–whether it’s a new economic report, or a war in Ukraine that indirectly affects the price of commodities (like gas/oil), or a pandemic that affects the price of so many other things–the market responds by adjusting its expectations for Fed rate hikes. Those expectations translate directly to how actual interest rates are moving. Fed speakers add fuel to this fire by confirming that the market is right to be afraid (both of rate hikes and balance sheet normalization). This paragraph, more than anything else in the newsletter, sums up the big problem for rates in 2022.

To be fair, it wouldn’t have been as big of a problem if the Fed had been more aggressive in combatting inflation in 2021, but policymakers were afraid of short-changing the economic recovery when new covid variant risks weren’t as well-understood. Even then, the Fed likes to move slowly and predictably. Unfortunately, that approach has proven to be extremely ill-advised given current market dynamics. That was already true before the Ukraine war, but doubly true after.

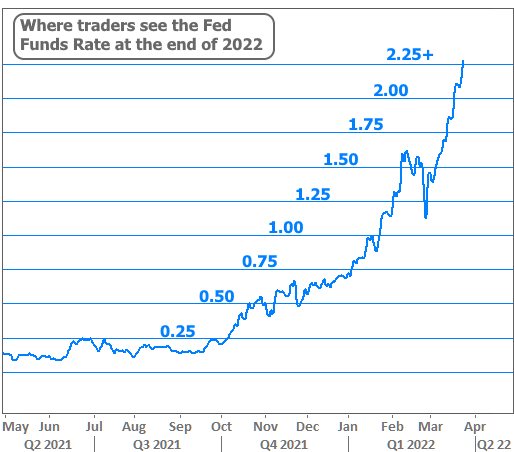

The result is a RAPID repricing of expectations as the market moves as quick as it possibly can to get in position for the Fed’s probably rate hike path. The following chart shows exactly how traders have been adjusting their bets on the Fed Funds Rate at the end of 2022.

This is an extraordinarily fast shift in rate hike expectations. With the Fed Funds Rate currently in the 0.25-0.50 bracket, it would require EIGHT rate hikes in the standard 0.25% amount to hit the year-end target. There are only 6 Fed meetings remaining! So at least 2 of those meetings will require a 0.50% hike. It’s been more than 20 years since we’ve seen a 0.50% hike. Now markets are expecting 2 of them in relatively short order. There’s even been talk of a 0.75% hike.

It’s this rapid repricing of expectations that makes things so volatile right now. Again, the Fed funds rate doesn’t directly dictate mortgage rates, but this unprecedented shift (complicated by the unexpected war in Ukraine) is sending shockwaves throughout the rate markets. Mortgages are taking some extra damage because they’re more reliant on Fed bond buying than Treasuries (and the Fed stated a preference to hold only Treasuries in the future. Double whammy!).

The net effect for mortgage rates is the fastest spike since 1994, assuming a time frame of several months. In terms of single week time frames, we figured the record set on Friday, June 21st, 2013 would stand for a long time and that nothing else would ever really come too close. The good news is that the record +(0.52%) still stands.

The bad news is that after this most recent Friday, the record JUST BARELY stands! The average lender moved higher by 0.49% this week. Considering mortgage lenders offer rates in set increments (.125, .25, .375, .5, etc) this is basically a tie. The average borrower would see a rate quote that is 0.50% higher this Friday vs last Friday in both occasions.

Moving beyond a 1 week time frame and nothing else in more than 25 years even comes close (you’d have to go back to 1994, and even then it’s a close call).

There is hope on the horizon, however. It may sound trite, but the higher rates go and the faster they get there, the sooner the next period of relative stability can begin. This can happen even as the Fed continues to hike rates because the mortgage and Treasury markets are making immediate changes based on future expectations. When the future plays out as expected, it doesn’t imply any change to the rates we’re currently seeing (indeed, it’s been the CHANGE in future expectations that’s hurt rates so badly).

This doesn’t mean rates won’t go any higher. But it does mean that they’ve clearly already put in a lot of work toward reaching their next peak. Any additional surprises will depend on incoming data and events–especially inflation related data and geopolitical events that greatly affect the outlook for growth or inflation.