Economic data is traditionally one of the key contributors to interest rate movement. Of the regularly-scheduled reports, none has more market-moving street cred than The Employment Situation–otherwise known as “the jobs report” or simply NFP (due to its headline component: Non-Farm Payrolls).

The relationship between econ data and rates can wax and wane. Covid definitely threw a wrench in the works, and economists still don’t know exactly how things will shake out. In general, the market is trading on the assumption that things continue to improve even if the data isn’t making that case today.

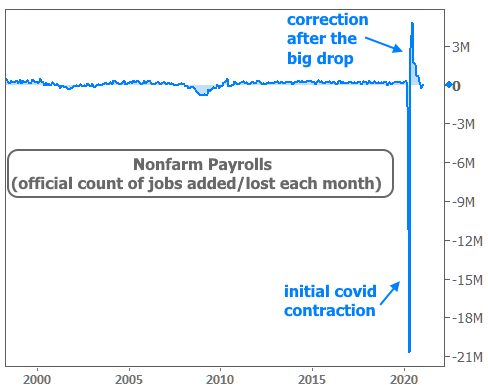

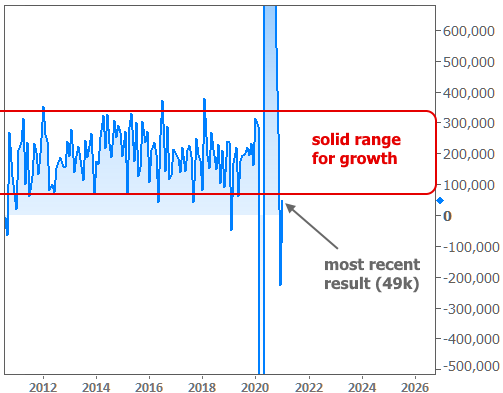

In fact, today’s jobs report specifically suggests something quite different. The economy only created 49k new jobs in January, and the last few reports were revised much lower to boot. Taken together, these reports effectively put an end to the “correction” phase of the labor market recovery.

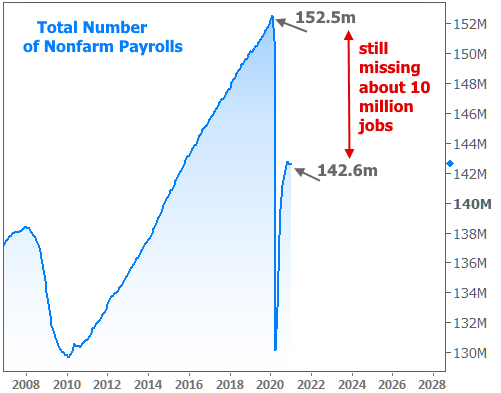

In other words, payrolls plummeted at the onset of covid (“contraction” phase). They’d been bouncing back in record fashion through September, but have since returned to closer to zero growth. That’s not great news considering we’re still roughly 10 million jobs away from pre-covid levels.

Based solely on the data above, interest rates shouldn’t be eager to rise. A 10 million job deficit is a big deal and it speaks to a level of economic activity that promotes risk-aversion (which, in turn, benefits rates).

But rates have other factors on their mind. In fact, we don’t even need to move on to other factors to consider one counterpoint. Simply put, the labor market recovery is still playing out. While it’s true we’ve seen the big contraction and correction, there’s a lot of uncertainty surrounding the coming months. It’s too soon to declare the death of the labor market based on the past few months–especially when seasonal adjustments are considered.

The following chart zooms in on the monthly job count to show the recent volatility and the normal range for solid job growth. One could easily imagine returning to that range as lockdown restrictions are eased and vaccine distribution improves. To a large extent, the bond market (and thus, interest rates) is operating based on its best guesses about the next 6-12 months as opposed to what it mostly already knew about January 2020. Bottom line: if job growth is going to end up in that “solid range,” we wouldn’t necessarily know it yet.

Moving on from jobs data, the bond market has other timely concerns. Next week brings another round of record-setting Treasury issuance. Treasuries = US government debt. The more money the government needs to spend (and the less revenue it takes in), the more Treasuries it must issue. The greater the issuance, the more upward pressure on rates–all other things being equal.

At the same time, congress passed a budget resolution that paves the way for the $1.9 trillion covid relief bill to pass in as little as 2 weeks. Stimulus hurts bonds/rates on two fronts by increasing Treasury issuance and by (hopefully) strengthening the economy. A stronger economy can sustain higher interest rates, in general.

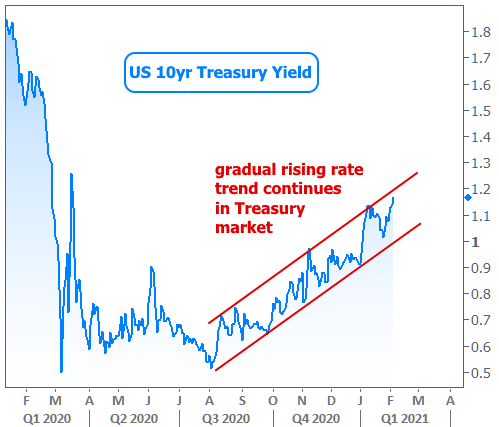

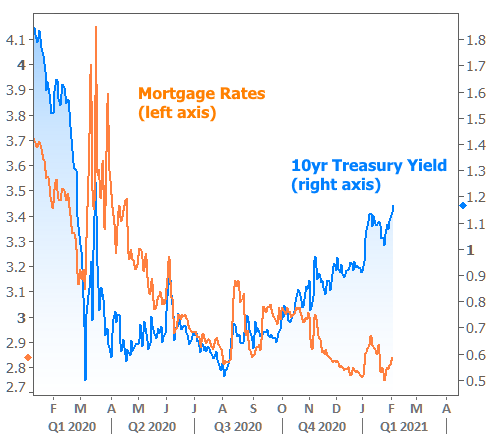

With all of the above in mind, it’s no great surprise to see a continuation of a well-established trend toward higher yields in 10yr US Treasuries. The 10yr yield is the benchmark for longer-term rates in the US and it tends to correlate extremely well with mortgages. As such, this chart would normally be a concern for the mortgage market.

But as we discussed last week, mortgage rates have diverged from Treasury trends in an unprecedented way.

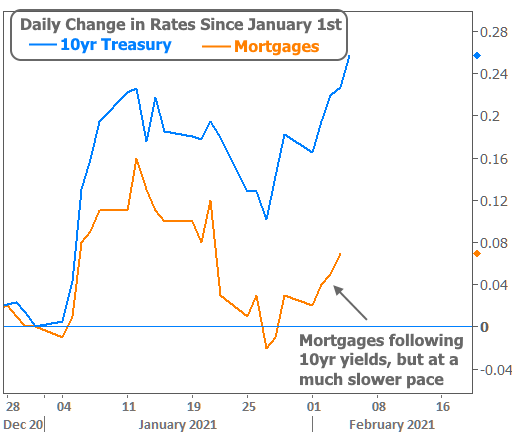

Despite the departure, the point of last week’s newsletter was to provide another reminder that mortgage rates can’t keep this up forever. Indeed, when we zoom in on the actual day-to-day changes in 10yr yields and mortgage rates, we can see strong correlation again–just with much smaller steps taken by mortgages.

The takeaway is that it’s no longer safe to bank on a series of increasingly lower all-time lows in mortgage rates. As long as the broader bond market remains under pressure, so too will the mortgage market–even if it takes less damage by comparison. If these trends continue, mortgage rates may not rise as fast as Treasuries, but they’d still be rising.

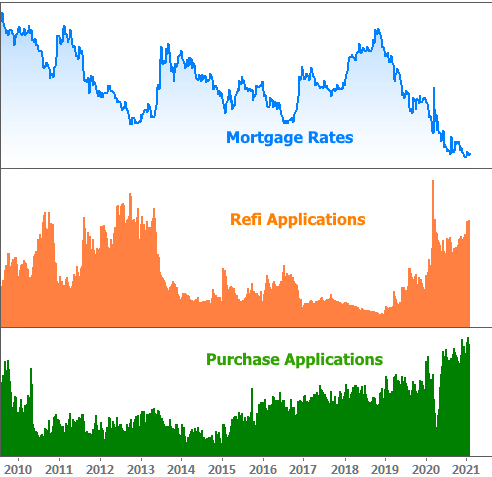

For now though, the sun is still shining on the mortgage market. Both purchase and refi applications are soaring, and new housing inventory can’t come fast enough.

Next week’s focal point for interest rates will be the Treasury auctions in the middle of the week–especially the 10yr Note Auction on Wednesday. Last time around, that auction marked a turning point for a rising rate trend that shared several similarities with the current one.