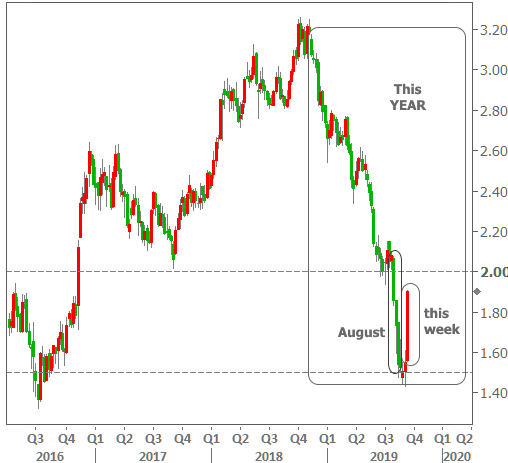

Remember the summer of 2013? Fans of low rates would rather forget it. Specifically, the 2nd to last week in June 2013 marked one of the most abrupt mortgage rate jumps on record. You’d have to go back to 1987 to see anything bigger.

The first week of July 2013 was the 2nd worst week of the past few decades and the decade’s only other example of a 0.30% jump in average mortgage rates… until now.

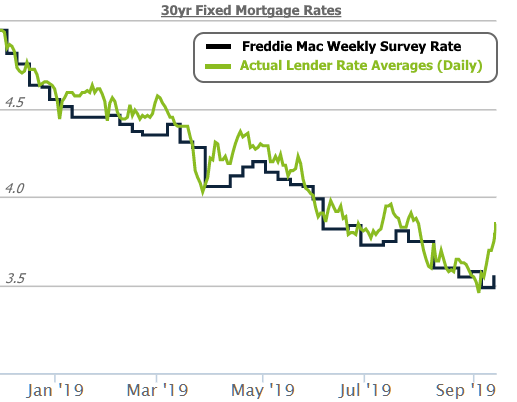

As of Friday afternoon (9/13/19), the average lender is quoting rates that are 0.30% higher than last Friday and nearly 0.40% higher than last Wednesday. Given that lenders generally offer rates in 0.125% (1/8th) increments, that means the average borrower is seeing an increase of 3/8ths of a point. Some are seeing a half point!

Few, if any, news articles or various mortgage rate indices have had a chance to catch up with the move. This is especially true of the widely cited Freddie Mac data that circulated on Thursday. It indicated a 0.06% increase in rates from the previous week. It was already significantly outdated by Thursday afternoon, but the gap between there and reality is now fairly staggering. Expect the black line to jump quite a bit higher next week!

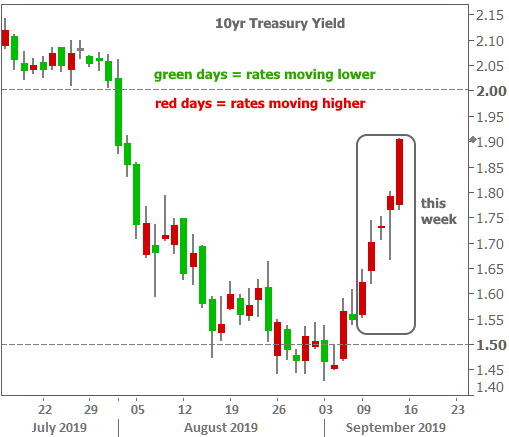

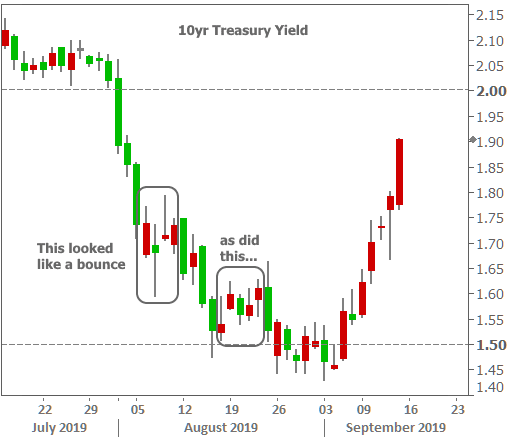

Here’s a closer look at movement in 10yr Treasury yields. Treasuries don’t directly govern mortgage rates, but they do set the tone for interest rate momentum overall. Each candlestick below represents 1 day of trading.

What happened to bring about this carnage? Was it something as epic as the June 2013 taper tantrum where the Fed first confirmed that it would begin winding down its bond buying program?

One of the things that made June 2013 so spectacularly terrible for rates was the fact that it was the first major correction after an unprecedented stay in a range of record low rates. For the most part, from November 2011 through May 2013, prospective mortgage borrowers had access to rates that were lower than at any other point in their lifetimes. In other words, the nature of the improvement that preceded it made 2013’s deteriorationmore abrupt. With that in mind, August was the best month and 2019 has been the best year for rates since 2011!

Quite simply, traders are worried that the overall rate rally has run its course. In fact, they were worried about that several times in August as well. On two occasions, traders began trying to push back in the other direction only for some unexpected news headline to come along and bring renewed downward pressure to rates. Now, finally, the reversal has taken root.

But why now? Why were rates finally able to not only achieve lift-off but to do so at such a blistering pace? There are several likely reasons. One of them has to do with a glut of bond market supply this week (supply pushes rates higher, all other things being equal), but that was more of a compounding factor.

The broader economy and the policy response of central banks is at the core of the issue.

When the Fed began to cut rates in July, many market participants saw it as the first of many, and the unofficial start of a policy easing cycle that’s often seen just before a recession. A nearly inverted yield curve (more on that in a moment), a seemingly escalating trade war, and general deterioration in global economic data only added fuel to the fire.

The first day of September’s big bad rate move coincided with events that cast doubt on that gloomy narrative. These included China’s commerce minister confirming the reopening of trade talks with the US and a very strong reading on a very important economic report. If the domestic economy was still showing signs of resilience AND if there was some additional measure of hope for a trade war resolution, perhaps it wasn’t quite time to bet on lower and lower rates after all.

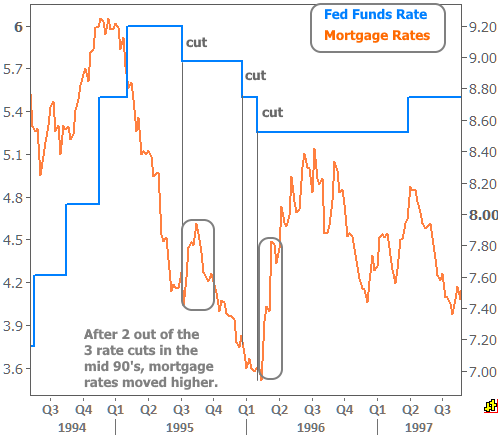

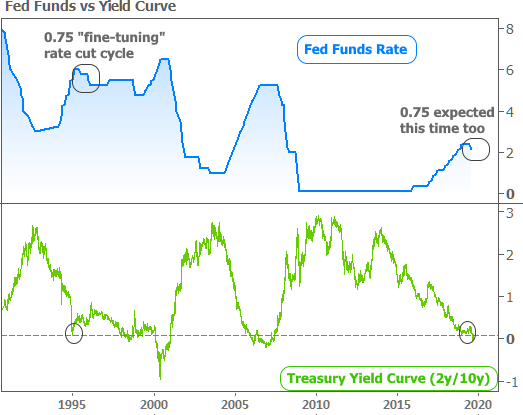

The following week (this week) compounded the issue with pundits calling for the European Central Bank to be slightly less aggressive with its easy money policies than initially expected. This dovetailed into questions about the Fed’s near term intentions. Rather than embark on a cycle of multiple rate cuts, perhaps we are instead seeing something similar to the mid 90s where the Fed cut 3 times only for the economy to do extraordinarily well for roughly 5 more years. Coincidentally, the Treasury yield curve was also nearly inverted then as well.

The yield curve is the line that plots the yields (rates) of various Treasury securities. But unless otherwise specified, it unofficially refers solely to the gap between 10yr and 2yr yields. Most of the time, 10yr yields are much higher than 2yr yields, but they will periodically switch places (i.e. invert). That inversion has been a relatively reliable sign that recession is on the way. 1994 was the most notable example of a nearly inverted yield curve that WAS NOT followed by a recession. Granted, there are plenty of differences between then and now, but the parallels are adding to the bond market’s anxiety.

Ultimately, the Fed’s decision to cut rates only 3 times in the mid 90s was predicated on an economy that no longer justifiedadditional rate cuts. This time around, the same conditions apply. Economic growth and inflation will have to stay steady or improve in order to prevent additional rate cuts and a general slide toward the next major economic contraction. No one knows how that’s going to play out just yet, and experts are increasingly lining up on both sides of the debate. That makes this an exciting time to follow economic data and the bond market. Big things are in the works for better or worse!

On a final note, keep in mind that next week’s probable Fed rate cut has absolutely no bearing on mortgage rates. The Fed onlymoves its rate when it meets once every 6 weeks. Mortgage rates, on the other hand, move every business day–sometimes multiple times. As such, mortgage rates have already long since accounted for the Fed rate cut (which is seen as 100% likely in futures markets).

While the rate cut itself won’t matter, the Fed’s verbiage and the updated economic projections can certainly have a big impact. The catch is that these other Fed events can push rates in EITHER direction. In other words, the Fed could cut its policy rate and mortgage rates could actually move higher. This has happened on multiple occasions in the past, and it happened after 2 out of the 3 rate cuts in the mid 90s.