No, this isn’t one of those click-bait headlines that promise to share “one weird trick” or proclaim “you’ll never believe what happened next.” Well, actually, some people might have a hard time believing this one.

In the interest of respecting the time of those who are already up to speed on this week’s economic data and interest rate movements, we’re about to talk about the paradoxical drop in rates despite decades-high inflation. Everyone else, read on!

Inflation is one of the mortal enemies of interest rates. Here’s why:

- Rates are determined by the amount of money investors are willing to pay for bonds/loans. Basically, investors give you a big chunk of cash and you make payments (with interest) over time.

- Inflation makes dollars less valuable (or, said another way, it makes “stuff” cost more).

- But the value of your stream of monthly payments never gets bigger because it was agreed upon upfront.

- As such, inflation makes your monthly payments less valuable over time (or less capable of buying “stuff”).

- Therefore, if the investor sees that inflation is increasing, they might raise rates today in order to realize a similar value from your stream of payments.

To take this example to the extreme, let’s say I loan you $100, and you make 11 payments of $10. I take each $10 payment and treat myself to the 3 taco combo at the taco truck once a month. Now let’s say that, due to inflation, the taco truck raises prices to $15. I have 2 choices. I can either get the 2 taco combo (and who wants to do that?!) or I can raise the interest rate on your loan such that the new monthly payment is $15.

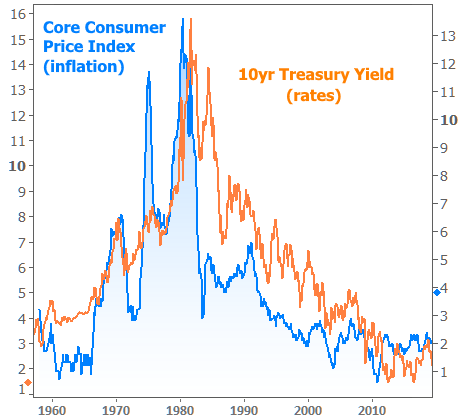

While it may or may not be driven by an insatiable lust for affordable tacos, it’s exactly this dynamic that accounts for the longstanding correlation between inflation and rates. Granted, inflation isn’t the only concern for rates, but it’s always a consideration. The following chart shows 10yr Treasury yields (the most popular benchmark for longer-term interest rates) and Core Consumer Prices (the most popular measure of consumer-level inflation).

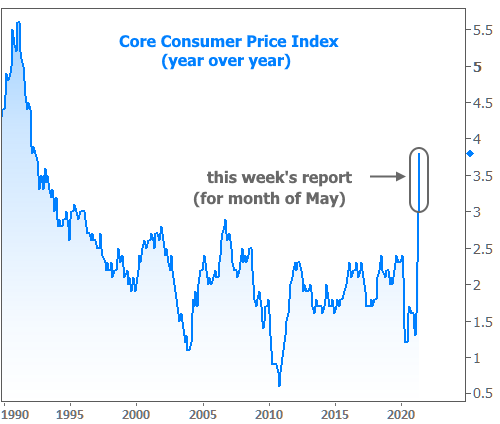

Actually, the most recent data is missing from the chart above. This week brought a new installment of the monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI). Much like last month’s report, it was a shocker, both in terms of how high the number was in outright terms and compared to expectations.

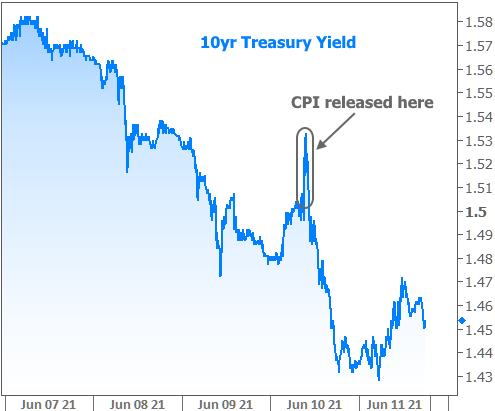

You’d expect interest rates to pay at least some sort of attention to such things, and you’d be right! But the attention was both minimal and temporary. The next chart shows how 10yr Treasury yields traded moment to moment this week. They did, in fact, pop higher right when the inflation data came out, but that didn’t last very long.

What’s up with the paradoxical reaction? While the average news headline suggested this “wasn’t enough” inflation to derail the Fed’s low rate policies, the actual motivation is far more esoteric. It has to do with an imbalance of trading positions in the bond market and the subsequent exploitation or punishment of that imbalance.

In market jargon, it’s known as a short squeeze. It happens when a majority of traders are betting on higher rates. They make those bets by shorting bonds. Shorting involves selling at today’s prices and buying back in the future at lower prices (side note: prices and yields/rates move in opposite directions, so lower prices = higher yields/rates).

If prices rise instead of fall, there is a certain line in the sand at which those traders will buy bonds to close out their position and avoid further losses. In so doing, they are only driving the price higher (or rates lower), likely forcing more short sellers to cover their losses by buying bonds. Call it a domino effect, a snowball, or a short squeeze. It all adds up to lower rates when it happens in the bond market.

Why were so many traders betting on higher rates? Well, it’s obvious, don’t ya know?! Covid numbers continue to fall. The economy continues to reopen. The Fed is increasingly thought to be considering tapering its bond purchases. And the the list goes on. Indeed, if we examine economic fundamentals, there are better cases to be made for rising rates vs falling rates.

Just one problem though: everyone knew these fundamentals were on the was at the beginning of 2021, and much of the logical rate spike occurred in anticipation of the economic reality we’re now witnessing. Moreover, the economy is still experiencing lots of growing pains as it heads toward wherever its going post-covid. We won’t have a clearer picture of the destination until this fall, according to the Fed. That makes “lower rates” a classic contrarian trade at the moment.

Does that mean rates will continue to fall for the next few months?

No one knows. Rates are capable of moving lower from here, but probably not exceptionally lower without some new, unforeseen shock. Rates are also capable of moving higher! But there too, probably not exceptionally higher until we get a clear indication that the economy has shifted into a higher gear on a more sustainable basis. When that happens–or even if it looks like it’s happening–that’s when we’re more likely to hear the Fed say they’re planning on tapering bond purchases.

That won’t be happening next week, but we could nonetheless see some volatility in rates after Wednesday’s newest Fed announcement. This is one of 4 Fed announcements that is accompanied by updated forecasts from Fed members (including the “the dot plot” that shows Fed rate hike expectations). Between that and Fed Chair Powell’s press conference, the Fed could send some sort of tapering message without actually putting it in writing.

One other wild card to keep in mind is the increased discussion among Fed members about the role their bond buying plays in real estate valuations. If they conclude that home price appreciation needs some help cooling down, they could adjust the balance of their purchases in favor of Treasuries. That’s a longshot for next week’s meeting, but if Powell speaks to it during the press conference, it would likely be bad for mortgage rates.

The press conference begins at 2:30pm Eastern Time, next Wednesday.