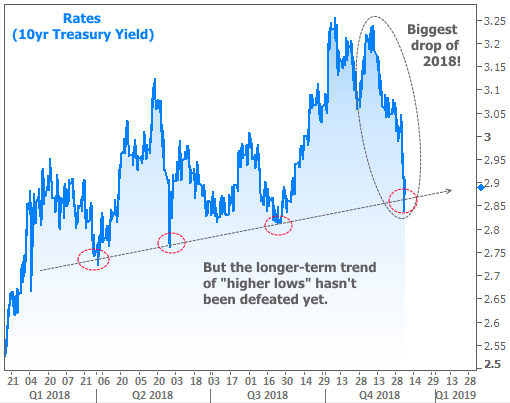

Last week’s newsletter asked whether or not the highest interest rates of this economic cycle are behind us. At the time, this was a relatively new and bold assertion. Now, this week makes that assessment look tame by comparison.

Specifically, rates surged triumphantly lower, and at a much quicker pace. From the recent highs, this is now the biggest, fastest drop in rates of the past 2 years. The counterpoints are that it took the highest rates in 7 years to set us up for these gains, and that 2018’s trend of “higher lows” remains intact.

Passing judgment on the significance of this drop in rates isn’t important though. What everyone wants to know is whether this is just a temporary bout of volatility or the beginning of a sustained move. To answer that, we’ll need to do our best to understand why the move is happening in the first place.

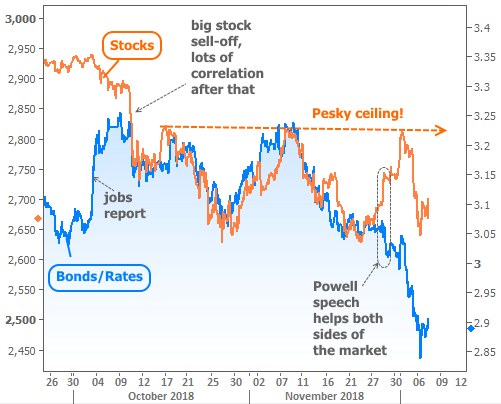

Given the volatility in stocks in October and November, that’s a good place to start. Indeed, stocks did more than anything to set the tone for bonds from early October through most of November. Notice how the orange and blue lines track each other almost perfectly during that time.

The correlation began to break down after last week’s Powell speech (which helped both stocks and bonds). Because of this, we can’t fully credit stocks for the big drop in rates. We can, however, examine how stocks are part of the equation.

There are always multiple factors underlying the ups and downs in stock prices, but there are also usually some general themes in play. The “pesky ceiling” in the previous chart is one of those themes. It speaks to the inability of the stock market to make a convincing move back up to September’s highs.

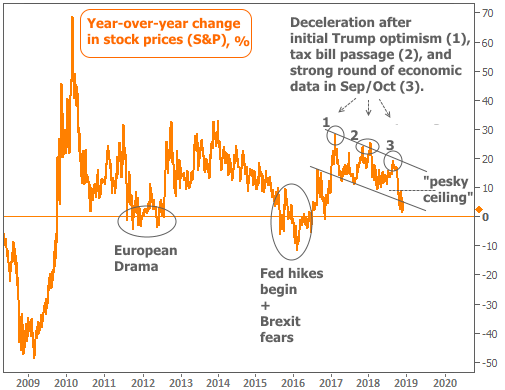

In the bigger picture, that pesky ceiling is reinforcing a broader deceleration in stock market gains. The following chart shows year-over-year percent change in stock prices. This measurement has only turned negative twice during this economic expansion: once when Europe seemed to be on the brink of a systemic crisis and once when investors worried that the Fed’s first rate hike (as well as Brexit) might hearken the end of what was already a long-lived economic cycle.

As the chart suggests, the presidential election provided a shot in the arm for the economic cycle. Most of this had to do with the tax bill, which was passed in early 2018 (coincides with the spikes in the “2” circle in the chart). Momentum flagged throughout the summer, but got another boost from strong economic data in September and October (“3” circle). That same data hurt interest rates due to fear that the Fed would need to hike its policy rate even faster.

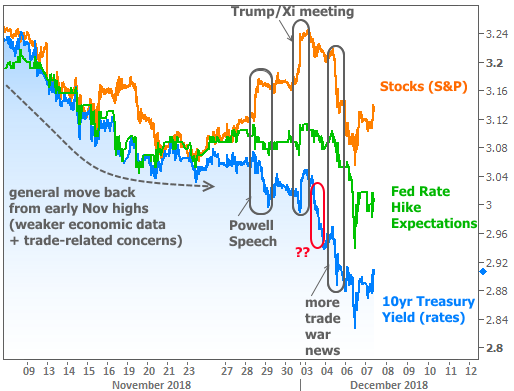

What a change one little month makes! Something happened in November and early December to cause a rapid reevaluation of that fear. The gradual part of the move is easily explained with a softening of economic data in November. Stocks, bond yields (rates), and Fed rate hike expectations were all able to lower their defenses. This can be seen in the dotted line in the chart below.

Clearly, things got a little crazy after that dotted line! The sideways movement (before the Powell speech) is a fairly typical part of the Thanksgiving holiday. After that, it’s not uncommon to see the next wave of momentum show up to set the tone heading into the end of the year. It just needed a catalyst. As we discussed last week, Powell’s speech served as that catalyst.

This week, however, things got more complicated. A meeting between Trump and Xi regarding US/China trade relations boosted stocks over the weekend and pushed rates slightly higher as of Monday morning. As additional details emerged from the meeting several days later, the weekend’s move was reversed (see the “more trade war news” caption in the chart).

But before that we have the mysterious move in Treasury yields (highlighted in red). This one didn’t coincide with a similar move in stocks or Fed rate hike expectations. Bonds were moving of their own accord (truly impressive considering the move began with rates already near their best levels in 2 months).

What could have motivated bonds to take off like this? There’s a reason for the question marks. This is one of those moves with no overt, singular motivation–even though it’s the most important move we’ve seen bonds make in a while. One thing we do know is that it was the first day of a new month, and that the activity in bonds really began to pick up right when US traders began making their first trades of the month.

This wouldn’t be the first time that the calendar has had a noticeable impact on markets. A certain portion of traders have to hold a certain mix of investments at the end of any given month. The beginning of the following month allows for some more flexibility, and it’s not uncommon to see momentum shift a bit right out of the gate. The fact that it shifted in a big, friendly way is what’s important. It let us know that traders had a bit of an agenda coming into December.

If we had to speak for that agenda, it would go something like this:

“OK, so the economic data was surprisingly strong in Sept/Oct, and it made some sense to worry about quicker rate hikes or higher long-term rates. But we all saw things cool down in November. We know this economic cycle won’t last forever. We know housing has increasingly acted as a drag. We can see that stocks aren’t eager to undo the damage sustained a couple months ago. We heard what Powell had to say last week about being closer to a neutral rate. We wouldn’t be crazy to expect the upcoming jobs data and Fed announcement to be less enthusiastic than recent examples. Considering all of the above, it may be time to start trading as if the long-term rate ceiling is behind us. We can’t yet know how far or how quickly rates might drop, only that it’s time to start thinking about pointing the ship in that direction.”

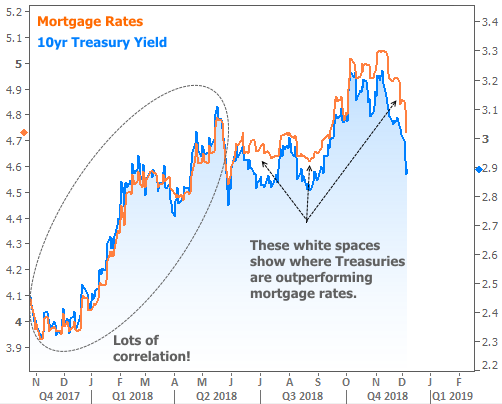

One caveat for any discussion about a rate rally is that mortgage rates are less able to participate than Treasury yields. This has to do with several factors, but chief among them is the fact that the Fed is now basically done buying mortgage-backed-securities as part of its reinvestment program. The takeaway is that mortgage rates won’t usually fall as quickly as the Treasury yields they typically follow. The silver lining is that mortgage rates have less to lose in the event Treasury yields move back up.