One of the most critical features of the modern mortgage market is the fact that mortgage investors can count on getting repaid even if the homeowner isn’t making payments. The mortgage servicer is the first line of defense, but it’s the agencies (Fannie, Freddie, Ginnie) that ultimately foot the bill if servicers can’t collect. Without this guarantee, investor demand would be much lower, rates would be much higher, and guidelines would be much tighter.

With ongoing unemployment claims soon to be 3 times higher than the previous record set in 2009, the percentage of homeowners looking to stop making mortgage payments has surged to in a way that was previously unimaginable in terms of both size and pace.

Mortgage investors have been rightfully concerned about the timeliness of payments. They know they’ll ultimately be paid, but money has value over time. To make the situation more relatable, just imagine your boss telling you “we’re not sure we can pay you this month, or next month, or maybe at all in 2020, but don’t worry! We’ll eventually get caught up.”

Why is this a problem for mortgage companies if the agencies guarantee timely payments? That’s a great question with a sobering, simple answer: they might run out of money!

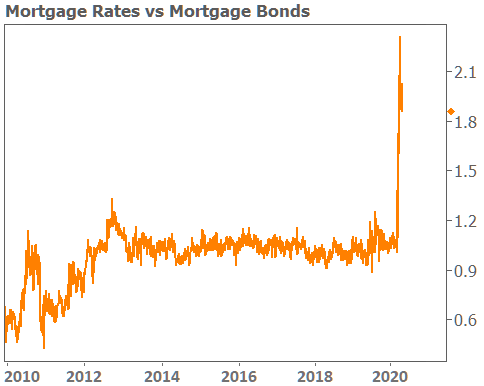

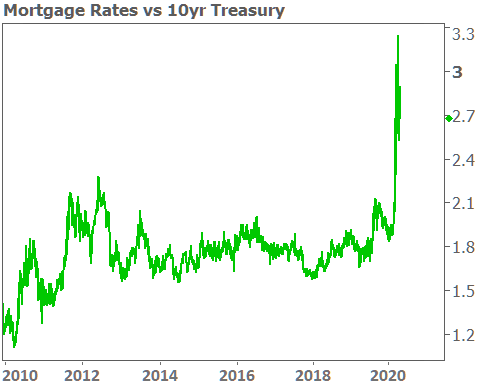

There are other issues too. One of the biggest is the question of how all of the new forbearances impact the value and saleability of mortgages on the secondary market. After all, these are assets that are definitely worth something. They’re often bought/sold/traded several times over the life of the loan. The uncertainty surrounding repayment is already hurting those values immensely, causing rates to be much higher than they otherwise would be and credit guidelines to be more restrictive.

Lastly, because mortgage servicers are required to uphold the timely payment guarantee until agencies step in, they’re facing a potentially overwhelming need for cash in the short term. This is a big problem for the non-bank servicers that comprise about half of the industry. They don’t have the same level of access to liquidity enjoyed by big, depository banks. If forbearance demand is high enough, several non-bank servicers could easily go under. There’s debate as to whether that would matter in the bigger picture and in the longer run, but there’s no debate that it’s causing big issues for rates and credit availability and rates at present.

This is why the mortgage industry has been clamoring for more definitive assistance from the government. The government’s response? In not so many words: TAKE A NUMBER!

It’s not that there’s a lack of understanding or empathy among policymakers. In fact, the first draft of the CARES Act (coronavirus relief bill) included a provision for mortgage servicers. That provision didn’t survive the senate, but that only made some in the industry expect an even better solution was in the works.

This wasn’t an outrageous expectation considering Treasury Secretary Mnuchin formed a task force dedicated to finding such a solution almost a month ago. 2 weeks later, Fed Chair Powell said he was watching mortgage servicers as a critical industry. At the same time, the Fed quietly removed the only line-item from its TALF program that could have helped mortgage servicers.

This likely meant the Fed was aware of a different option in the works. Either that or they’d simply decided it would be premature to offer liquidity to an industry whose cash flow crunch was still on the horizon while other industries had much more pressing concerns.

For two additional weeks, all we had was speculation and anticipation. But as of this week, everything was made clear: the mortgage market is on its own for now and it will take a lot more drama to get the government’s bigger guns involved (Treasury/Fed). How do we know this? Mnuchin flat-out confirmed it, noting that regulators had already taken sufficient steps to create liquidity.

That’s a reference to a previously announced program from FHA/VA regulator Ginnie Mae and two key policy updates this week from Fannie/Freddie regulator FHFA. The FHFA updates were technically “liquidity measures” for the mortgage market (here are the details), but unofficially, they’re nails in the coffin for hopes of more meaningful support from policymakers, at least for now.

How could newly announced liquidity measures be bad? One simple reason: if the FHFA is running point on helping the mortgage industry, it means the Fed/Treasury is not, and that’s where the more meaningful support would have come in.

Fannie and Freddie (the GSEs) are already on the hook for a shortfall in servicer advances. They’re not bringing any new money to the table. True, they’ve temporarily lifted their restriction on buying/guaranteeing loans that enter forbearance right after closing but that’s a negligible percentage of the broader forbearance problem.

The GSEs are also charging enough of a premium that many lenders will simply keep the loans on their own books if they have the capacity. As such, the seemingly generous offer is really more of a pawn shop type of scenario for the most desperate mortgage servicers.

And that’s just the good news…

The bad news is that FHFA specifically excluded cash-out loans from this offer. In the 2 days that followed, multiple lenders discontinued cash-out programs or significantly raised costs. This is true even for a borrower with 50% equity and an 800 FICO.

If there’s a consolation, it’s that all of this is fairly logical. Yes, the mortgage market has officially been told to take a number, but there are certainly people, businesses, and industries that are in greater need of direct attention from the Fed/Treasury.

Bottom line: we should expect guidelines to get tighter and rates to remain elevated on certain programs until the massive wave of forbearances has clearly subsided or until the problem has grown dire enough that policymakers have no choice but to respond more forcefully.