Things are changing rapidly in the mortgage market. Almost overnight, loan programs have disappeared, interest rates are all over the place, and more than a few lenders are closed for business indefinitely. All this despite the Federal Reserve buying more than $100 billion / week of mortgage debt. Is this another meltdown?

In many ways, the current situation is far worse than the 2008 meltdown. Credit is evaporating more quickly. Mortgage rates aren’t as responsive to Fed bond buying. Borrower income/employment demographics have imploded much more decisively and much more suddenly. And the average mortgage servicer is facing a wave of homeowners unable or unwilling to make their mortgage payments that is both many times larger and infinitely more condensed than the 2008 meltdown ever imagined.

Evaporating Credit: You can’t get that kind of loan anymore.

Loan programs that were widely available just a few weeks ago are suddenly nowhere to be found. Other programs, while still available, have risen in cost so much as to effectively be discontinued. Even in the world of the highest quality, least risky conventional loans, some lenders are having a hard time keeping cash flowing quickly enough. They’ve been forced to raise rates, delay fundings, or temporarily halt operations.

Fed Bond Buying Isn’t a Magic Pill.

In the past, when the Fed bought mortgage bonds, rates plummeted quickly. This time around, although the Fed is filling a vital role for the mortgage market, rates have problems that the Fed can’t fix.

Mortgages’ Most Important Asset, Gone.

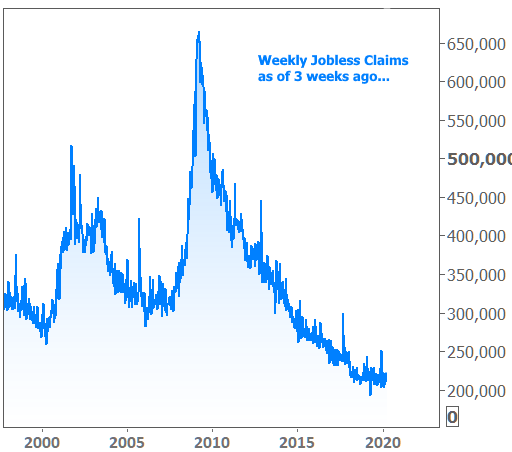

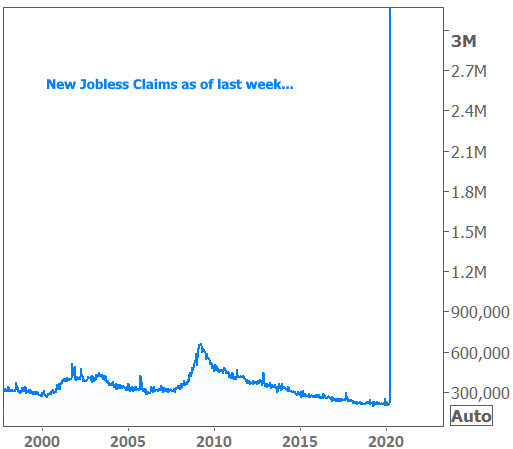

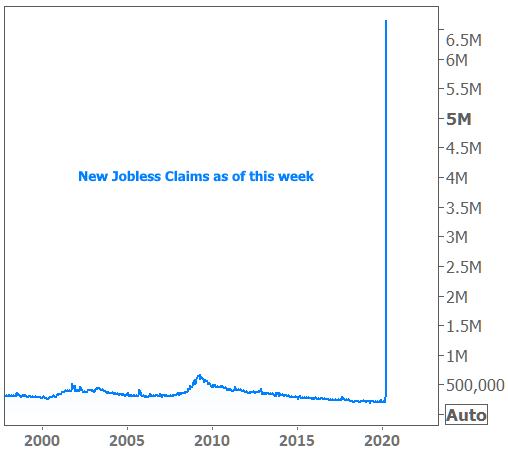

If there’s one thing that’s more important to a mortgage than anything else, it’s the homeowner’s ability to make payments. In turn, those payments depend most critically on employment. We’re now witnessing the biggest, most abrupt onslaught of joblessness in human history. It’s no wonder the mortgage market is scared.

The Forbearance Tsunami, and the Breaking of the Mortgage Market

The CARES Act encourages homeowners to request a forbearance (a break from making mortgage payments) in cases where their ability to pay has been impacted by coronavirus. At the same time, it prohibits lenders from verifying a borrower’s income has indeed been affected. If one thing is responsible for the breaking of the mortgage market, this is it.

Why? Because many will skip payments simply because they can. Combine them with those who’ve actually lost jobs (or those who soon will) and the mortgage market is facing a bigger, faster drop in payments than the worst doomsday scenarios ever imagined by mortgage bankers.

This forbearance tsunami is actually at the root of all the other issues listed above. Mortgage investors have no interest in rolling the dice and hoping some government bailout or epidemiological breakthrough will quickly enable homeowners to begin making payments again. They have no faith they’ll see their cash again in a timely way.

Under a more normal dire scenario, mortgage servicers would continue to forward at least the interest portion of payments to the investor (principal too in many cases). If servicers couldn’t pay, investors could be made whole by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or Ginnie Mae, the huge housing agencies that stamp investor guarantees on a majority of mortgages in the US.

Under this dire scenario, investors have no faith that servicers and agencies have remotely enough cash on hand, should some forbearance predictions come true. There too, the uncertainty of predicted outcomes is a problem unto itself. Even if investors knew they’d get their money back, they still have no way to know what the timing or profit would look like.

All of the above makes investor buying demand for mortgages dry up. Demand for the riskiest, most costly programs dries up first. Unfortunately for borrowers needing a government loan (FHA/VA/USDA), servicers of those loans are required to pay investors BOTH principal and interest on time, even if homeowners aren’t paying. As such, this group has seen some of the biggest changes in availability and biggest spikes in rates.

It’s worth noting that Ginnie Mae (the agency that guarantees these government loans) has all but promised a backstop facility will be in place for servicers soon. In that same announcement, they also acknowledge that the backstop alone wouldn’t be enough for some scenarios and that they continue working on other solutions. That’s not the sort of thing that fills a mortgage investor with confidence, even if it’s significantly better than no gameplan at all.

Until investors can have more confidence and more certainty about how they’ll be repaid, they are being extraordinarily cautious. That means the amount of dollars available to fund mortgage loans will be much lower than normal and rates for certain programs will be much higher. It also means that no amount of mortgage bond buying from the Federal reserve is going to fix the system or force rates back to all-time lows.

So, Does That Mean This is Indeed Worse Than 2008?

In many other important ways, 2020 is MUCH better than 2008. The mortgage market didn’t cause the coronavirus pandemic. The average mortgage leading up to 2020 was much higher quality than those seen in 2005-2007. Incomes documentation, employment verification, improvements in home valuation transparency, and unified underwriting standards mean that whatever meltdown we’re about to see will not need to be blamed on the mortgage or housing market.

In other words, we’re not facing down a housing/mortgage crisis that destroys confidence in the entire system for years to come. We’re facing down an ‘everything’ crisis that merely happens to be sweeping up housing/mortgages in the tide of ill effects.

That’s not to say the road ahead won’t be bumpy or that things won’t get worse before they get better. But whereas the mortgage market was destined to endure more pain for a longer time than the broader economy in 2008, the swiftness of our recovery this time around will only be limited by the swiftness of our fight against the pandemic. Indeed, many housing and mortgage market participants will be eager to get back to business when America gets back to work.