From a strictly economic standpoint, this week saw the release of several impressive reports. It just so happened the 3 best reports were also the 3 most important reports (based on their typical ability to cause a reaction in financial markets).

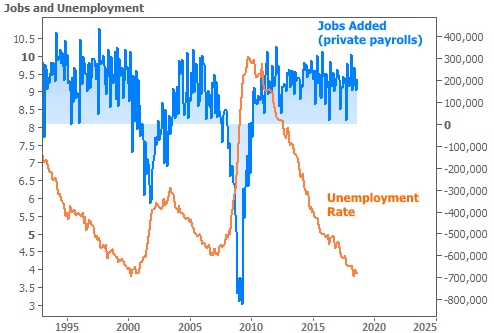

Chief among these was the big jobs report on Friday. This contains multifaceted data but the two traditional headlines are “nonfarm payrolls” (NFP… a tally of jobs created) and the ubiquitous unemployment rate. Both metrics did quite well this week and both continue playing key roles in an uncommonly long economic expansion.

Abundant employment is always a good thing, right?

In general, that’s true, but there are some losers when the economy is chugging right along. Interest rates have a long history of rising in response to stronger job creation. In fact, the NFP number has been the single most important piece of economic data for rates over the years.

Lately, however, strong job creation has grown to be somewhat of a given. Due to the severity of the great recession, experts aren’t too surprised to see the economic expansion lasting so long or doing so well. Simply put, we had a lot of catching up to do.

In terms of prompting market movement, NFP has been a mere shadow of its former self over the past few years. Instead, rates have been more interested in other data thought to hold the key to the next big shift in the economic cycle.

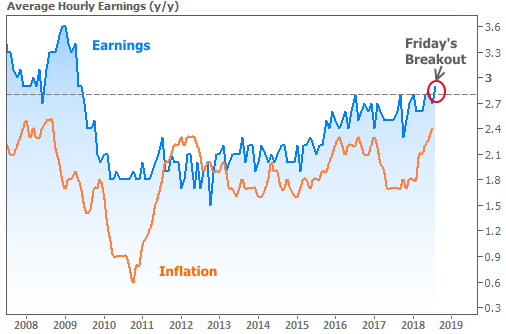

To that end, inflation and wage growth have been hot topics. Even the Fed has taken note of what they consider to be “a puzzling lack of wage growth.” To be clear, the Fed isn’t saying wages aren’t rising–simply that they’re not rising as quickly as past precedent would suggest. The Fed typically doesn’t spend too much time thinking about wage growth, but in the current case, they see it as a precursor to inflation–something they think about constantly.

As luck would have it, the big jobs report also includes average hourly earnings–an important measure of wage growth. Earnings have struggled to move above 2.8% year-over-year. They were only expected to hit 2.7% this week, but ended up rising to 2.9%. This isn’t the first time they’ve tried to break the 2.8% ceiling recently, but the previous attempts were revised lower while this one has a chance to stick. The tacit implication would be more upward pressure on inflation.

If wage growth does indeed “stick” and if inflation rises as a result, it would be bad news for rates. Inflation is sort of an arch-nemesis for interest rates for the following reasons:

- Rates are based on bonds

- Bond investors are paid back a predetermined amount of dollars.

- If inflation is high, those dollars won’t buy as much in the future as they would today.

In short, inflation subtracts some of the rate of return from bonds. If investors see inflation rising faster than expected, they would simply demand higher rates to offset the inflation risk.

This week provided a clear example of investors quickly demanding higher rates of return in response to data that impacted inflation expectations. As soon as the strong wage data came out, rates rose at the fastest pace of the week. To put things in perspective, an important manufacturing index hit a 14 year high on Tuesday and the resulting rate spike was nowhere near as big.

Bottom line: jobs are good. Manufacturing gains are good. A strong economy is good. Unfortunately for stakeholders in the mortgage/housing markets, a strong economy logically coincides with rising rates. The past decade has seen more exception to that rule than at any other time in modern economic history due to the rate-friendly influence of the Fed’s bond buying programs and other accommodative policies. Now that the Fed is successfully hiking rates and reducing its bond holdings, longer-term rates (like mortgages) are increasingly feeling the pressure.

That’s nothing new. Between the outlook for Fed policy and government spending (gov. spending = Treasury supply = lower Treasury prices and higher Treasury yields, aka “rates”), bond investors have been pushing longer-term rates higher for several years. They’re arguably ahead of the game or close to it, at least when it comes to these 2 big factors.

But when it comes to other factors like inflation and wage growth, bond investors can’t plan ahead nearly as well. They’re more beholden to evolving data. If that data is breaking above key ceilings as seen in the wage/inflation chart, rates must increasingly consider breakouts of their own.